Exhibition

The ‘Theresienwiese’ in Munich – famous as the venue of the largest Volksfest beer festival and fair in the world – was the scene of a right-wing extremist bomb attack in 1980. For 234 people, an evening at the ‘Wiesn’ on 26 September ended in an act of brutal violence.

The Oktoberfest bomb attack is the worst act of terrorism in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany. Nevertheless, it has been virtually eliminated from the collective memory. The reasons that led to this act have still not been clarified in full to this day and possible accomplices not brought to justice.

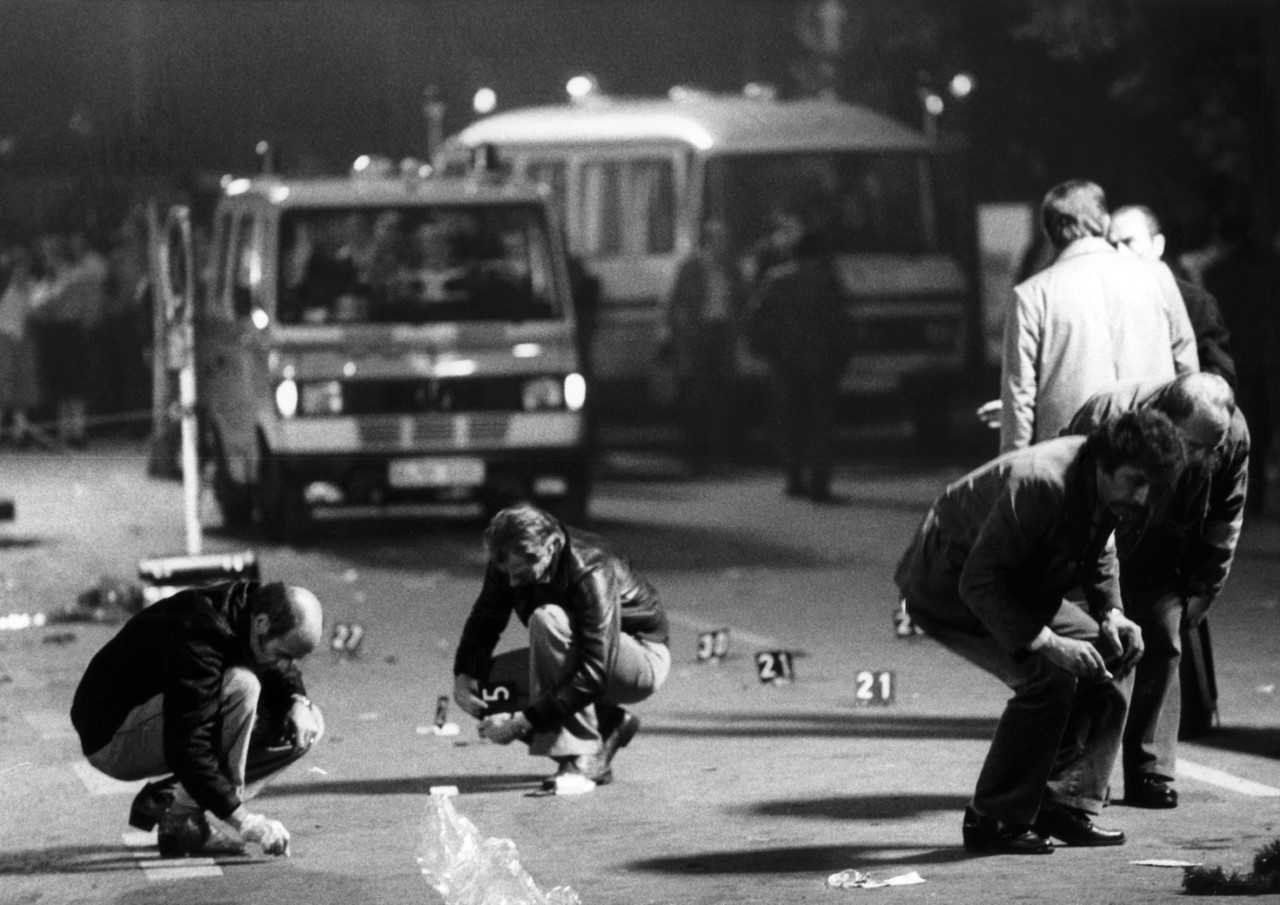

Friday, 26 September 1980, 10.20 pm: Thousands of visitors to the ‘Wiesn’ were on their way home when a bomb exploded at the main entrance to the Oktoberfest site, sending out a blinding, darting flame. The force of the blast threw people to the ground within a radius of 20 metres. Metal shards were blasted in all directions with devastating consequences. A large number of first responders, police officers and members of the rescue forces immediately took care of the injured onsite. 13 people died; 221 were injured, 68 of them badly.

The police were soon able to identify the perpetrator as the student Gundolf Köhler, a right-wing extremist. He had placed a homemade explosive device in a litter bin and was killed in the explosion.

After the scene of the attack had been examined and cleaned up, the Oktoberfest reopened for business the following morning.

The general public and the media initially showed great sympathy for those who had survived the attack. This was reflected in the considerable donations of money and items. By the end of 1981, private individuals and companies from all over the Federal Republic had donated around two million DM. On top of this came 200,000 DM from the City of Munich. A further 500,000 DM was made available by the State Government of Bavaria.

The ‘unbureaucratic help’ promised by politicians reached some people quickly; others only after intensive efforts. To date, appropriate material compensation that goes beyond non-cash benefits to alleviate injuries and that takes the victims’ histories of suffering over decades into consideration has yet to be made.

Many survivors reported difficulties with the public authorities. Health-related complaints were played down, long-term effects not recognised and applications for necessary treatments rejected. Feeling reduced to the level of a supplicant, many have refrained from applying for benefits to this day.

Only in 2020 has the classification of the act by the federal authorities as an extreme right-wing attack expanded the prospect of an appropriate compensation for survivors.

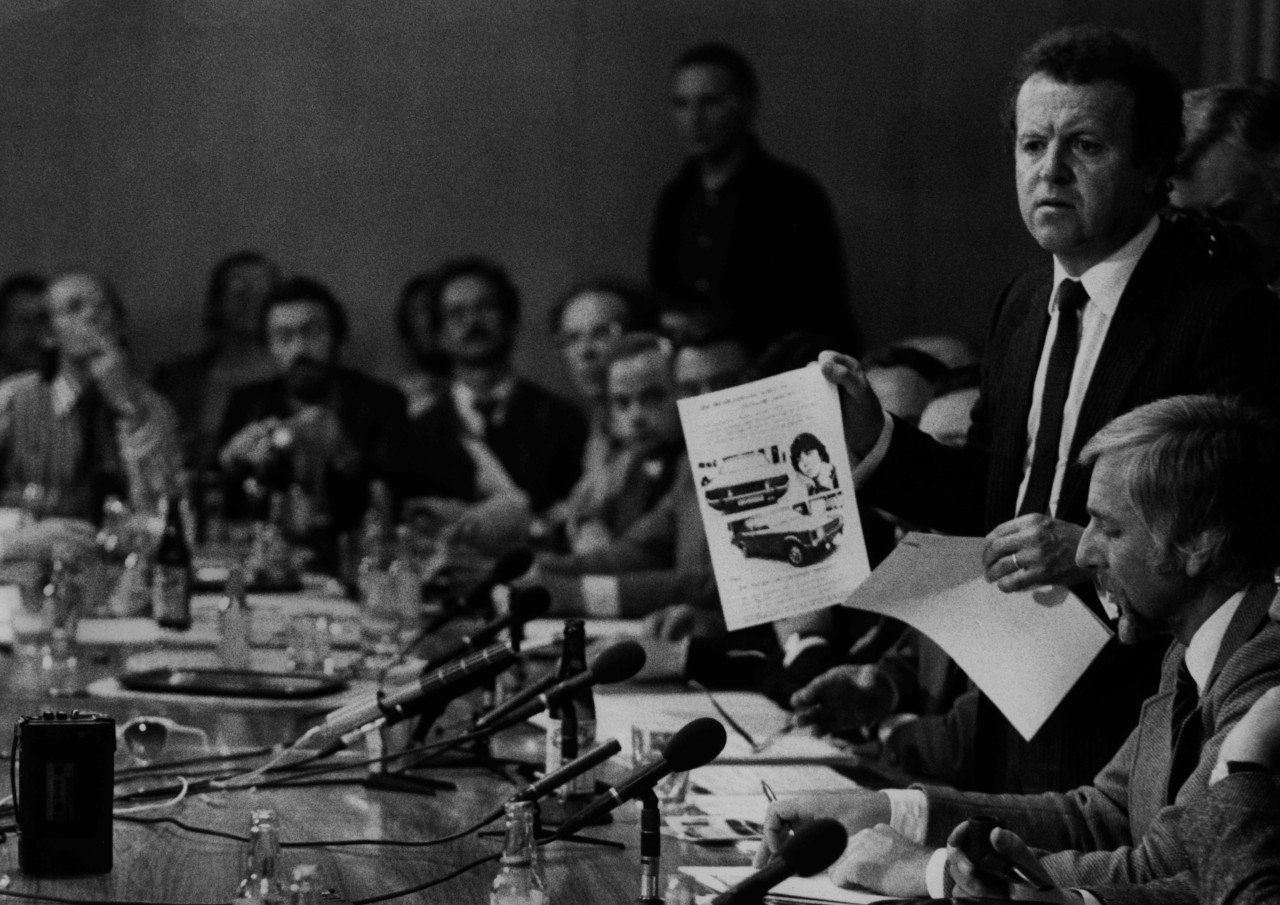

On the morning after the attack, the police already knew of the perpetrator Gundolf Köhler’s extreme right-wing profile. His activities in the neo-Nazi scene were known to the security agencies. Further investigations, however, did not bring other accessories or accomplices to light. The final report of 1982 classified the attack as a personal act of desperation, pushing the perpetrator’s political convictions into the background.

Survivors, their legal representatives, journalists and political groups challenged the result of the investigation. For a long time, they protested, in vain, against the verdict and found increasing support from the general public. When new evidence emerged about possible accomplices in 2014, the authorities resumed investigations.

Even if the renewed questioning of witnesses has put a huge strain on survivors, many have called for a detailed clarification of the events surrounding the terrorist act.

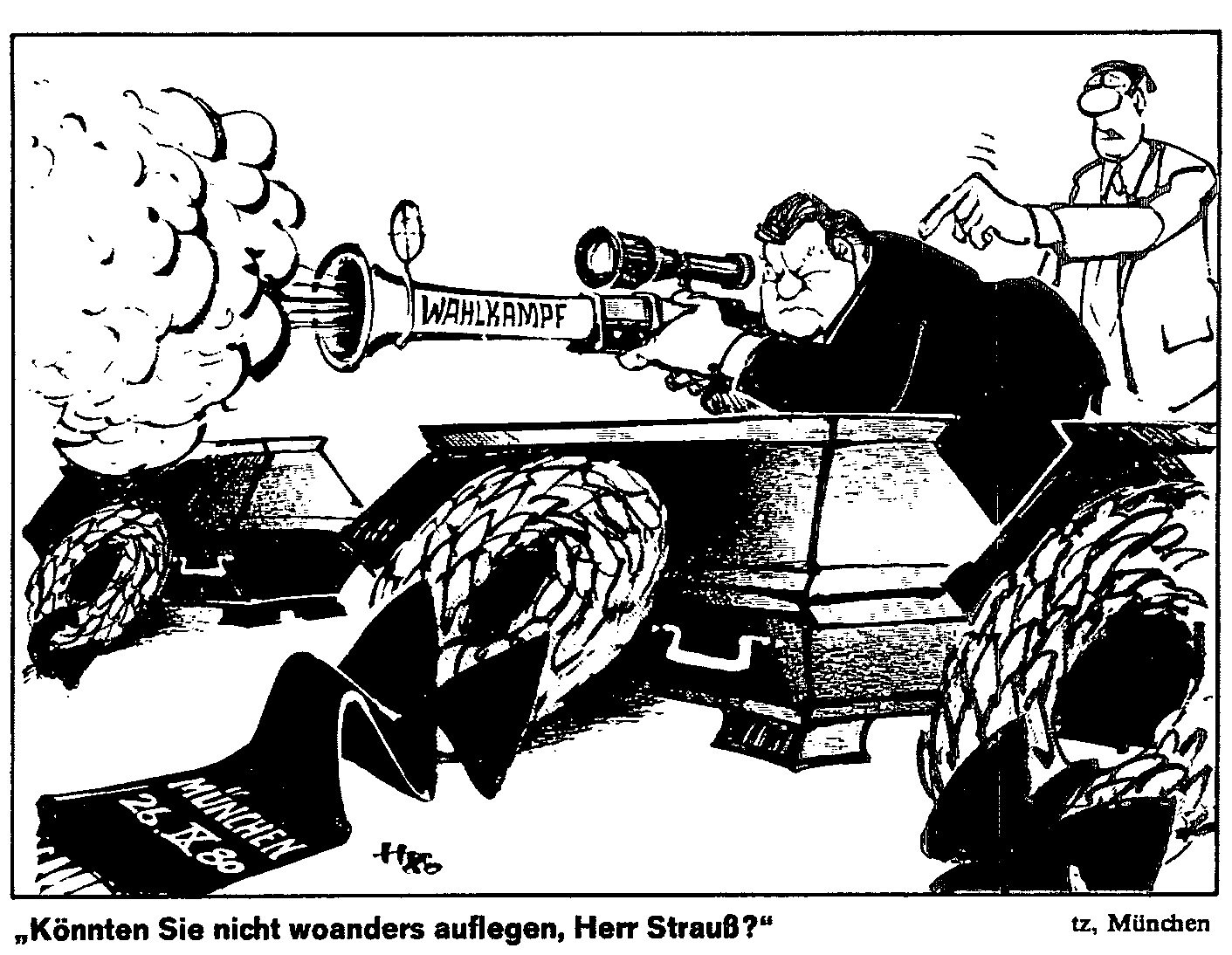

The bomb attack happened one week before Bundestag elections in 1980 and immediately became a topic in the election campaign. The attempt by the Bavarian State Government to divert attention away from their own failures greatly damaged investigations.

Pivotal questions remained unanswered: Where did the military explosives come from? Were others involved in building the bomb or were they with Gundolf Köhler at the scene of the crime? Questions for which forensic science today would have been able to provide information. However, fifteen years after initial enquiries were concluded, hundreds of pieces of evidence and possibly DNA traces and other clues, were destroyed by the authorities.

From today’s perspective, the scale of right-wing terrorism failed to be recognised as a threat to democracy at that time. By keeping to the depoliticised, single bomber theory extreme right-wing networks were not confronted resolutely enough.

How should a democratic society react to an attack such as that at the Oktoberfest? In 1980 the ‘Wiesn’ was closed uniquely for one day of mourning.

The City of Munich had difficulty finding an appropriate response. By contrast, politically active groups such as the ‘DGB-Jugend München’ remembered the victims every year on 26 September and demanded resolute action against right-wing extremism.

On the first anniversary the City of Munich unveiled a bronze stele in memory of the victims. However, it does not place the act in a political context nor does it bear the names of those killed. These were only engraved on it years later at the insistence of the victims’ relatives.

Despite repeated remodelling at the entrance to the ‘Wiesn’, no suitable way was found to remember the survivors as well, or shed light on the attack. The City of Munich has been addressing these shortcomings since 2015 and, in dialogue with contemporary witnesses, compiled this documentation.